Grindr Profiles

The map shows the project documentation. Click for interactive view.

Grindr as a Demographic Research Tool: Residence, Lifestyle, and Self-identification in NYC

Grindr Profiles delves into the urban queer experience during 2020-2021 by examining Grindr users in New York City. This project focuses on their lifestyle documentation and online self-identification, incorporating users' profiles and statistics obtained from Grindr's attribute-identification system.

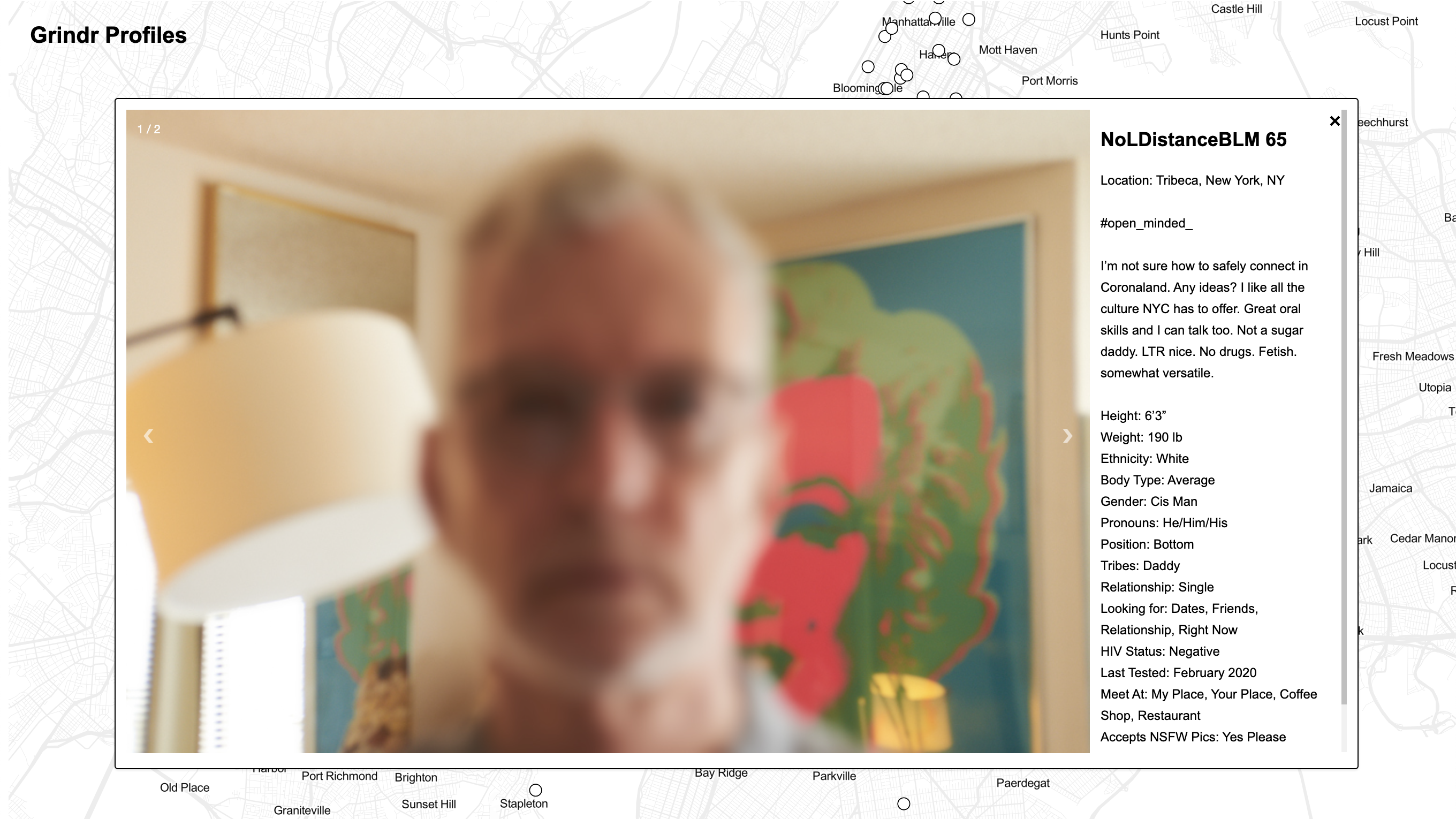

Encompassing a diverse range of 195 participants aged 19 to 75, the profiles represent all five boroughs in New York City. Each profile includes a headshot of the participant (privacy protected with a blur), a photo of their living space, proximate geolocation of their home, and public profile information.

Introduction

A user's living space.

Dating apps have become an integral aspect of social life this decade. In response to the lack of social interaction during the COVID-19 lockdown, the use of dating apps rose dramatically compared to the pre-pandemic era.[1] In light of the spike in active users and a decrease in urban mobility and transportation, dating apps functioned as an alternative census, providing up-to-date data on a particular population during the period.

Grindr, a GPS-based dating app with 3 million daily users,[2] has been the most popular gay mobile app since its launch.[3] In its free version, the interface shows up to 100 nearby profiles in a 3-column scrollable grid. By providing live profiles sorted by measurable distance, Grindr is known for its insecure data exposure.[4]

Driven by isolation like many others, I downloaded Grindr during the lockdown in March 2020. My impression of Grindr came from the thumbnail presentation of nearby users, with the distance of each profile appearing alongside their name and age. Upon tapping a headshot thumbnail, the profile expanded to include a display name, age, and a brief “about me” introduction describing the user. During COVID, this section was often filled with “No mask, no sex” and a virus emoji. A list of statistical attributes from body type to sexual position, ethnicity,[5]relationship status, expectations, gender identity, and HIV status followed. The idea for this project was born out of checking Grindr during the lockdown.

From the thumbnail display, I noticed that each neighborhood had its own spatially bounded ecology. There was a group of fit, nearly identical white men in their early 30s aggregated in Williamsburg; individuals with mismatched lifestyles juxtaposed in West Harlem; young creatives with “they/them” pronouns and Telfar bags on racks huddled in Bushwick. Social divides on Grindr included a hybrid of fashion trends, physical appearance, word choice, home interiors, and the neighborhood they choose to live in. I began thinking about how dating app users might reflect spatial identity in a condensed, diverse city like New York. I figured it would be insightful to document people through Grindr, from a marginalized angle, to project a bigger society. Grindr evades certain boundaries by allowing people to encounter those they might not otherwise meet in real life. The immense geographic spread of Grindr’s user base made it efficient for reaching out to participants and collecting users’ data. How do people live behind their online profiles?

Taking an investigative approach, I started inviting users to participate by photographing their residences and collecting their online profiles through mass sampling across the city. With a neutral self-portrait and a brief project description on my profile, I sent the same message to thousands of people over a year on a daily basis: “Can I photograph you and your place?”.

Headshots from all participants.

Afterword

As a photographer and a user myself, I want to understand the underlying reasons that bring people together on this platform at a particular place and moment. The research question has an open-ended answer. It shoots a firework into the sky and results in endless sparks. Although the project has a social science inclination, I would view it as an experimental art practice. Nonetheless, I believe that photography and mapping can holistically address the empirical gaps that arise from the decoupling of art from social science.

It would be a stretch to come to unequivocal conclusions about a given neighborhood based on the data collected. This project seeks to look at the queer community as its members present to one another internally, not for outside perception and study. The complexity of queer life and New York City is beyond my comprehension. The role of this project is more of a demonstration than a representation.

My thought on dating apps is that they mirror society. The existence of Grindr profiles evidences a dimensional urban landscape: a looking glass that reveals thumbnails on smartphone screens, users behind them, places where events happen, and the neighborhoods where the profiles populate, altogether. The year-long observation has documented the intricacies of human movement, lifestyles, and virtual representations in New York City’s Grindr population. How do people live behind their online profiles? This project offers a sparkle of answers.

Methodology

The project started in July 2020, was postponed briefly during the winter of 2020 due to the surge of COVID-19, and concluded in August 2021. The sample was a geographic convenience sample in the chosen locations. There were several ways to collect participants. Simple random sampling was the first step to reach out to general individuals. The collection method turned to representative sampling if the initial result deviated too far from local demographics.[5:1] In some cases, references from previous participants were accepted if subjects were difficult to find (i.e., snowball sampling), especially if they lived in a private neighborhood or were locally less numerous minorities. The locations for sampling were parks, pharmacies, MTA stations, Link NYC kiosks, and other populous sites in public spaces.

195 Grindr users participated. Participants ranged from 19 to 75 years old, living, working, or studying in New York City for at least two months. There were 85 participants from Manhattan, 77 from Brooklyn, 18 from Queens, 13 from the Bronx, and 2 from Staten Island. Races and ethnic groups included white, Black, Latino, Asian, Middle Eastern, South Asian, and others. Genders included man, cis man, trans woman, trans man, nonbinary, and queer. The majority of them had public profiles with identifiable headshots.

The process began with messaging multiple users at once, asking on Grindr, "Can I photograph you and your space?" for participation. If a user expressed curiosity, I would further explain: "It's my personal photo project about Grindr’s demographics. I photograph people’s living spaces and a blurry headshot of them." After they agreed to participate, we would schedule a photoshoot at their living space—living room, bedroom, or studio, and I would ask permission to include their Grindr profile information. The photoshoot lasted between 15 to 30 minutes. The incentives were a cup of coffee or a free portrait session. Participation was often voluntary without asking for anything in exchange.

There were some immeasurable factors that might have affected participation. First, despite New York being a metropolis, outlying and industrial areas with low population density still exist, making convenience sampling ineffective and inaccurate. Second, social status might impact the willingness to participate; for example, occupation, religion, or family structure all bear on attitudes toward the community and visibility therein. I do not have direct evidence to link the relations between socio-economic factors and participation, but my supposition comes from my lived experience and my general awareness of the community. Third, Grindr attracts certain people with common motives than every queer individual; there were some levels of overrepresentation since many participants expressed more open-mindedness than the general public. Fourth, my public Grindr profile and my personal look could affect participation. I do not know if my Asian features would give me more or fewer participants in different scenarios.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks for the information, correction, and critique given by the following individuals: Madeline Carpentiere, Travis LaCouter, Max Levin, Juan Madrid, Nicolas Marquez, and Dani Sandler. A lot of great ideas came from editing and conversing with them.

Thanks to James Shi for technical support on my website. Thanks to friends who let me stay at their apartments to collect participant data day and night and gave me suggestions for where in their neighborhoods to explore.

In particular, I am most grateful to my participants for their absolute kindness, trust, and openness. Many ideas and feedback came directly from my participants with their questions about the purpose and findings. The project would not have been possible without every participant’s help.

I acknowledge the final result might not always look pleasing to everyone, including my participants. It is crucial to stay honest with both myself and my participants. I avoided displaying too-specific data to keep participants anonymous and out of potential harm. Anonymity is the principle of the project; although some participants are more identifiable than others based on their circumstances.

Finally, thanks to viewers who have gone over my project. I hope it brings you new thoughts.

References

Meisenzahl, M. (2020, August 5). These charts from Match Group show more people are turning to online dating during the pandemic. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/tinder-hinge-match-group-dating-apps-more-users-coronavirus-2020-8 ↩︎

Smith, C. (2021, May 30). Grindr statistics, user counts, and facts. DMR. https://expandedramblings.com/index.php/grindr-facts-statistics/ ↩︎

Horvat, S. (2016). The Radicality of Love (p. 24). Polity. ↩︎

Franceschi-Bicchierai, L. (2021, July 22). Grindr has been warned for years about its privacy issues. Vice. https://www.vice.com/amp/en/article/wx57nm/grindr-has-been-warned-for-years-about-its-privacy-issues ↩︎

Ethnicity is not a correct term based on Grindr’s classification. There are only “white, Black, Latino, Asian, South Asian, Middle Eastern, Native American, Mixed, and other” on the list of options. Race is a more proper term in this case, although it is more so a self-identification than scientific truth. ↩︎ ↩︎